To avoid mishaps, the London Underground has long provided “Mind the Gap” visual and auditory warnings to passengers to be careful when crossing the gap between the station platforms and the trains. Is this relevant to The Bahamas? It should be. We would do well to identify and mind the gap or gaps that can significantly delay our progress to the sustainable future we desire, immobilize it or altogether put paid to our chances for meaningful advancement.

As its blueprint for progress, The Bahamas chose to become a signatory of the United Nation’s “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, the 17 goals of which are as follows:

1) No Poverty, 2) Zero Hunger, 3) Good Health and Well-being, 4) Quality Education, 5) Gender Equality, 6) Clean Water and Sanitation, 7) Affordable and Clean Energy, 8) Decent Work and Economic Growth, 9) Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure, 10) Reducing Inequality, 11) Sustainable Cities and Communities, 12) Responsible Consumption and Production, 13) Climate Action, 14) Life Below Water, 15) Life On Land, 16) Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions, 17) Partnerships for the Goals.

These focal points have been summarized as five ‘P’s: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace and Partnership.

By its subsequent declarations on the subject, one can assume that the nation has engaged the journey to achieve these highly desirable goals. In March of 2017, The Bahamas Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Immigration hosted the UN Bahamas Symposium on Implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Small Island Developing States (SIDS). In his address to the participating country representatives, the then prime minister Perry Christie, declared, “My Government, like all others here, has prioritized the implementation of the 2030 Agenda.”

On 11 April, United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed said that “the clock is ticking” down, to making the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. She invited participants to “reflect honestly about where we are falling short, because those shortcomings are also where the opportunities lie to make a difference”.

So, how is The Bahamas’ score card looking almost four years past the 25 September 2015 adoption of Agenda 2030, with just 11 years left on the agreed timetable? For one thing, it has been acknowledged by government and the wider community that quality in education is far from homogenous and significantly lacking in many areas in state-run schools. We have been assured that the Ministry of Education has undertaken major revisions to the national curriculum. The Ministry has yet to make the general populace party to the proposed changes.

The energy programme is better defined, although sorely assailed by the internal challenges of Bahamas Power and Light, which supplies electricity to more than three-quarters of the population of the Bahamas archipelago. The immediate drive, however, is towards stabilizing generation and distribution by installing new oil-fuelled generators and revolutionizing governance and administration. More positively, as relates to conservation goals, government has signed contracts for LNG generation and passed laws in support of alternate energy sources, particularly solar generation on the individual level.

Against great odds, particularly the adversarial relationship between the workers’ union at Bahamas Water & Sewerage Corporation and its administration, there is satisfying evidence of a government plan to regulate the inconsistencies in the performance of this vital utility in the supply of clean water.

Of note, the government is making appreciable moves to upgrade the healthcare system and, as recently reported, is exploring a partnership with Johns Hopkins Medicine to ensure that new developments are world class.

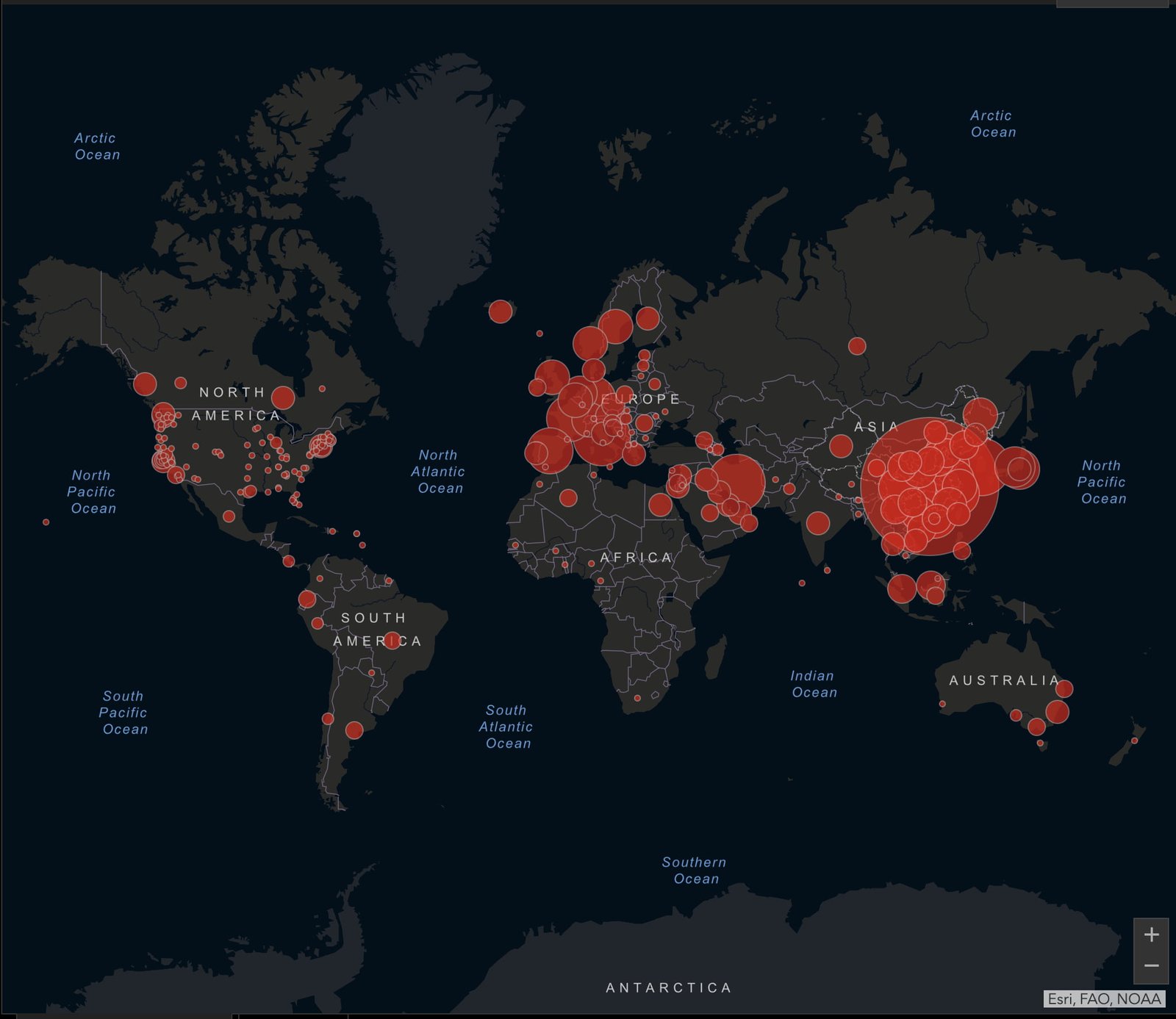

The picture in marine conservation is even more positive—and necessarily so. As Bahamas Reef Environment Educational Foundation (BREEF) put it so succinctly:

The sea comprises about 95% of The Bahamas’ geographical area. Moreover, with 2200 miles of coastline, our marine environment is a significant part of our natural and cultural heritage. Healthy marine ecosystems enhance our biodiversity, influence our cultural expressions and provide economic benefits through our tourism, fisheries, maritime and education sectors.

Happily, The Bahamas is blessed with a number of strong and dedicated non-governmental conservation organizations (Bahamas National Trust, BREEF, The Nature Conservancy, Ocean Crest Alliance, a bevy of local and international scientists and divers and a population that is becoming more aware of the need for protection of its marine assets. Moreover, government is more active than ever before in designating Marine Protected Areas and taking measures to protect specific fauna. In 2014, even before the promulgation of Agenda 2030, government established a closed season for the culturally and economically important Nassau grouper. Additionally, there is recognition and certainly a major push from conservationists to establish active conservation of conch, which is as valuable to the Bahamian way of life as the grouper. As expected, the push back from sectors of the fishing industry has been intense.

It is essential to note that the summary of Agenda 2030 begins with people. It makes sense that human beings are the purposive and bonding elements and the engine of the plan, the goals connecting to their integration into this farsighted design for sustainable development. Point 4 of the resolution coming out of the 2018 Rio Conference reaffirmed “the need to achieve sustainable development by promoting sustained, inclusive and equitable economic growth, creating greater opportunities for all, reducing inequalities, raising basic standards of living, fostering equitable social development and inclusion, and promoting integrated and sustainable management of natural resources and ecosystems that support, inter alia, economic, social and human development while facilitating ecosystem conservation, regeneration and restoration and resilience in the face of new and emerging challenges.”

Just recently, United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed has noted, “The transformation we need requires us to acknowledge that everyone is a development actor…”

In the realm of economic integration, most laudable and promising has been government’s 2018 initiation and funding of the Small Business Development Centre. At the time, Prime Minister Hubert A Minnis commented, “We took as a guiding principle, sustainable economic growth should be driven by Bahamian investment, and creativity, in tandem with strategic foreign direct investment…We believe that entrepreneurs are the primary drivers behind innovation and growth.”

In close connection, it is pleasing to note the rise in young people, particularly millennials, in engaging innovative entrepreneurship and global outreach.

On the other hand, the poverty reduction strategies are still largely based on government aid rather than the dignity of being treated as an actor of equal importance in one’s uplift. In The Bahamas, poverty reduction needs a paradigm shift informed by a simple truth as expressed by UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova: “Inequalities are multi-dimensional, multi-layered and cumulative…understanding and acting effectively on inequalities requires looking beyond disparities of income and wealth to capture their political, environmental, social, cultural, spatial and knowledge features.” (International Social Science Council Report [2016])

Another statement beautifully amplifies the latter statement:

Inclusion is community. No one becomes included by receiving handouts, even if these handouts are given by public bodies and with public resources. No one becomes included by being treated by a program in which they are no more than a number or a statistic. Inclusion is connection to the network of community development, it is to become more than a speck of dust, to have a forename and surname, with one’s own distinctive features, skills and abilities, able to receive and give stimulus, to imitate and be imitated, to participate in a process of changing one’s own life and collective life. (Busatto, Cezar. 2007 “Creating Inclusive Society: Practical Strategies to Promote Social Integration”, contribution to the Expert Group Meeting)

The Bahamas claims democracy and, indeed, enjoys many freedoms, but they should not be bestowed at the whim of government, but held and cherished as intrinsic rights. It is in creating the channels that will allow its citizens purposeful political inclusion where Bahamas action has been sluggish. Clearly lacking is the political will to legislate such necessary rights as gender equality and to bring into force the Freedom of Information Bill, both of which could give the populace a stronger and better informed and directed voice in the nation’s decision-making. This is a significant gap that requires minding.

We need to promote the kind of equality across the board that does not treat people the same but meets people where they are and gives them the same opportunities to succeed despite their differences. It is in the activation or neglect of the informed popular voice and informed community action, which will significantly influence the quality of The Bahamas’ gains in sustainable development for the benefit of its own people and for the country’s contribution to the global patrimony.

We have to start “minding the gap”—those essentials of sustainability that we have neglected or ill-served to date.