Stan Lee was a seminal part of Miya Crummell’s childhood. As a young, black girl and self-professed pop culture geek, she saw Lee was ahead of his time.

“At the time, he wrote ‘Black Panther’ when segregation was still heavy,” said the 27-year-old New Yorker who credits Lee with influencing her to become a graphic designer and comic book artist. “It was kind of unheard of to have a black lead character, let alone a title character and not just a secondary sidekick kind of thing.”

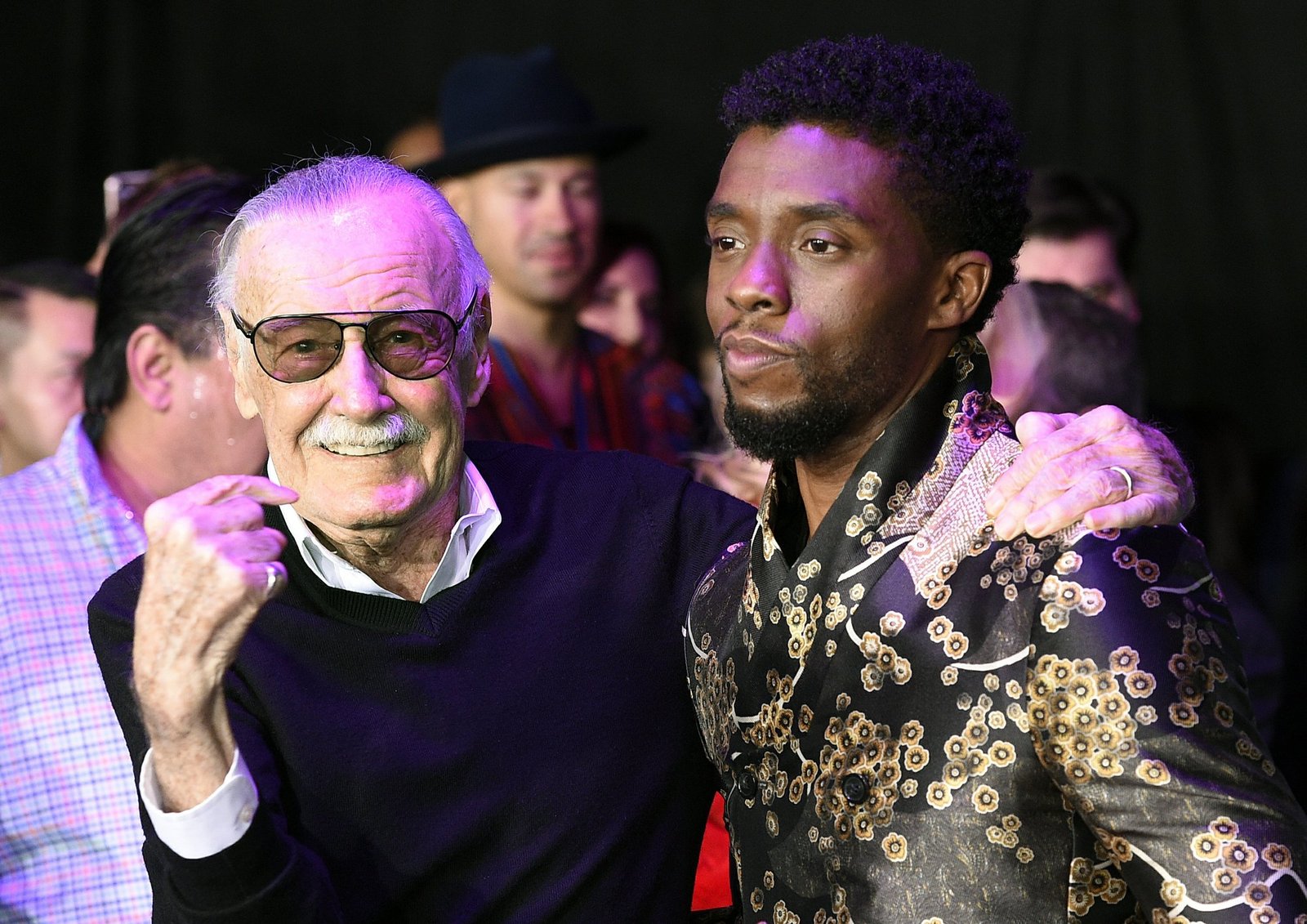

Lee, the master and creator behind Marvel’s biggest superheroes, died at age 95 on Monday. As fans celebrate his contributions to the pop culture canon, some have also revisited how the Marvel wizard felt that with great comic books came great responsibility. When black people were risking their lives in the 1960s to protest discrimination where they lived and worked, Lee enacted integration with the first mainstream black superhero. Black Panther, along with the X-Men and Luke Cage, are on-screen heroes today. But back then, they were the soldiers in Lee’s battle against real-world foes of racism and xenophobia.

As fans celebrate Stan Lee’s contributions to the pop culture canon, some have also revisited how Lee felt that with his comic books came great responsibility. (Nov. 14)

Under Lee’s leadership, Marvel Comics introduced a generation of comic book readers to the African prince who rules a mythical and technologically advanced kingdom, the black ex-con whose brown skin repels bullets and the X-Men, and a group of heroes whose superpowers were as different as their cultural backgrounds.

The works and ideas of Lee and the artists behind T’Challa, the Black Panther; Luke Cage, Hero for Hire; and Professor Xavier’s band of merry mutants — groundbreaking during the 1960s and 1970s — have become a cultural force breaking down barriers to inclusion.

Lee had his fingers in all that Marvel produced, but some of the characters and plot lines “came from the artists being inspired by what was happening in the ’60s,” said freelance writer Alex Simmons.

Still, there was some pushback by white comics distributors when it came to black heroes and characters. Some bundles of Marvel Comics were sent back because some distributors weren’t prepared for the Black Panther and the kingdom of Wakanda developed by artist and co-creator Jack Kirby.

“Stan had to take those risks,” Simmons said. “There was a liberation movement, and I think Marvel became the voice of the people, tied into that rebellious energy and rode with it.”

Lee also spoke to readers directly about the irrationality of hate. In 1968, a tumultuous year that saw the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Lee wrote one of his most vocal “Stan’s Soapbox” columns calling bigotry and racism “the deadliest social ills plaguing the world today.”

“But, unlike a team of costumed super-villains, they can’t be halted with a punch in the snoot, or a zap from a ray gun,” Lee wrote.

Marvel’s characters always were at the forefront of how to deal with racial and other forms of discrimination, according to Mikhail Lyubansky, who teaches psychology of race and ethnicity at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. With the X-Men, many readers saw the mutants, ostracized for their powers, as a commentary on how Americans treated blacks and anyone seen as “the other.”

“The original X-Men were less about race and more about cultural differences,” Lyubansky said. “Black Panther and some of the (Marvel) films took the mantle and ran with the racial issue in ways I think Stan didn’t intend. But they were a great vehicle for it.”

Some of the efforts to break out minority characters haven’t aged well. Marvel characters like the Fu Manchu-esque villain The Mandarin and the Native American athletic hero Wyatt Wingfoot were considered groundbreaking in the ’60s and ’70s, but may seem dated and too stereotypical when viewed through a 21st-century lens.

“It’s interesting. Stan Lee kind of takes the credit and the blame, depending on the character,” said William Foster III, who helped establish the East Coast Black Age of Comics Convention and is an English professor at Naugatuck Valley Community College in Waterbury, Connecticut.

Foster, who started reading Marvel Comics in the 1960s, said even doing something as minor as including people of color in the background was monumental.

“Stan Lee had the attitude of ‘We’re in New York City. How can we possibly not have black people in New York City?’” Foster said.

Blacks began taking on the roles of heroes and villains. Foster said some characters may have been seen as “tokenism” but that’s sometimes where progress has to start.

In 10 years, the Marvel Cinematic Universe films have netted more than $17.6 billion in worldwide grosses. The “Black Panther” movie pulled in more than $200 million in its debut weekend earlier this year. Next year, actress Brie Larson will take flight as “Captain Marvel.” An animated movie centered on Miles Morales, a half-black and half-Puerto Rican teen who inherits the Spider-Man suit, will drop next month. And there continues to be interest around Kamala Khan a.k.a. Ms. Marvel, the first Muslim superhero.

“I had a lot of white friends growing up,” said freelance writer Simmons, who is black. “We watched ‘Batman’ and we also watched ‘The Mod Squad.’ My personal belief is that if you put the material out in front of folks and they connect with it, they are going to connect with it.”

For many fans and consumers, it’s about the product not the skin color or sexual orientation of the character, he added.

Crummell, the comic book artist, said she thinks representation for minorities and women in comic books is improving.

“I think now, they’re seeing that everybody reads comics. It’s not a specific group now,” Crummell said. “It’s not just African-American people — it’s women, it’s Asians, Hispanic characters now. I would credit Stan Lee with kind of breaking the barrier for that.”