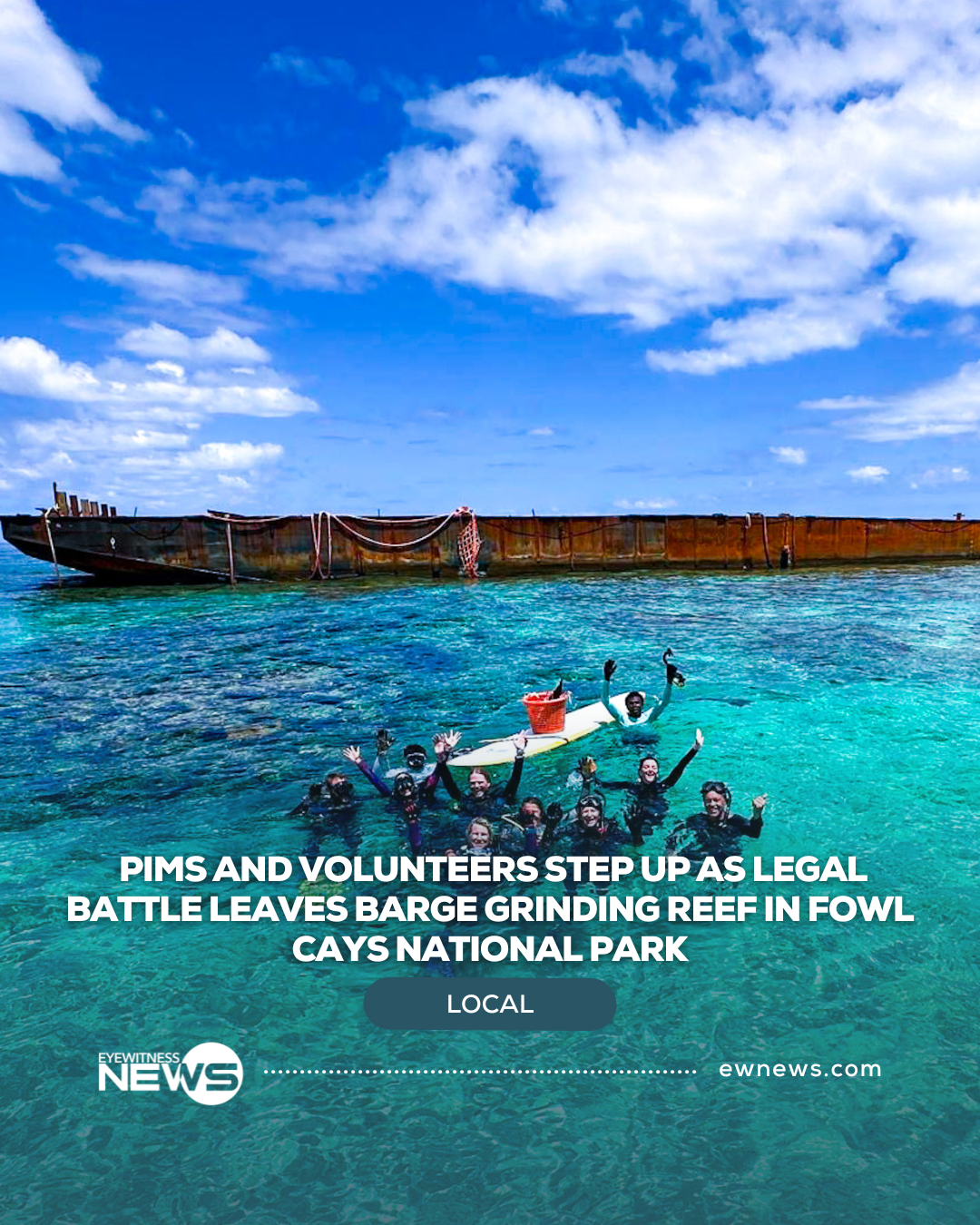

ABACO, BAHAMAS — This week saw the second volunteer-led cleanup of the stranded tug and barge in Fowl Cays National Park—an ordeal that has dragged on for more than a year with no resolution in sight. As the owners remain conspicuously absent, the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) once again mobilized local residents, divers, and conservation partners—including the Bahamas National Trust, Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation, Friends of the Environment, and the Department of Marine Resources—to remove debris from the reef, underscoring the public’s growing frustration as corals that took decades to flourish continue to be ground away.

Backed by more than five decades of marine research and community engagement around the world, PIMS pairs cutting‑edge science with on‑the‑ground action—restoring reefs and mangroves, mapping habitats, fostering sustainable fisheries, and training ocean stewards through programs like the Reef Rescue Network. That expertise is now driving the cleanup effort in Fowl Cays and community-centered action for a reef in crisis.

According to recently revealed Supreme Court filings, Executive Marine Management Services was hired in March 2024 by the multi-billion-dollar Baker’s Bay development to transport sand and stones from Freeport to Great Guana Cay. The company, in turn, subcontracted the tugboat from FowlCo Maritime and Project Services to tow its barge. When the tug and barge ran aground on March 26, 2024, the Port Department formally ordered both parties to remove the wreck. Instead, their dispute spiraled into a $5 million-plus lawsuit, leaving the barge to batter the reef while the matter drags on in court.

On the ground in Abaco, local residents have been left to deal with the aftermath. “Every time the wind and waves come up, the tug and debris from the barge shift and scatter ropes, twisted metal, and building materials that choke our corals and threaten marine mammals,” explains Ms. Denise Mizell, Abaco Program Manager for the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS), who is leading volunteer dives at the wreck site. “We see the damage firsthand every time we dive—and it only gets worse when the weather turns.” PIMS, a global nonprofit committed to protecting and restoring ocean life, stresses that a full salvage operation is desperately needed before the reef suffers irreversible harm.

“This is our second major cleanup in 2025, and since we don’t have funding for this work, we’re entirely dependent on the generosity of our volunteers,” says Mizell. “I’m so grateful to them because it’s an enormous undertaking. We aren’t a salvage company, but we’re doing what we can to protect the reef from further damage.”

Over a long day underwater, volunteers logged more than two hours per diver wrestling with debris. “We finally moved one massive metal frame,” Mizell says. “It took four divers—fins off—walking the sandy seafloor to carry it. We burned through three hacksaw blades yet cut only half the rope. One surface‑support volunteer waited on a paddleboard, and every time we freed a length of line, we draped it over the board so he could paddle it back to the boat.”

On Tuesday, DMR and BNT boats, as well as a local boat captain and volunteers, ferried divers to the wreck site. Troy Albury of Dive Guana donated scuba tanks, G&L Ferry donated the freight for the tanks, Marsh Harbour Boat Yard provided temporary space for debris, and homeowners on Elbow Cay offered vessels such as the Sweet Sue to carry people and equipment. Jim Todd, a medic with the Hope Town Volunteer Fire Department, stood by for diver safety. Young voices are also driving the effort, including volunteers Antoine Russell and Davonte McKinney of the Bahamas National Trust, who believe saving these reefs is vital for Abaco’s future.

“We all have a responsibility to protect these waters,” says McKinney, one of BNT’s snorkelers and surface support. “If we let the reef crumble, we’re losing more than coral—we’re losing the life and livelihood of our community.”

Divers were shocked by how deeply sand from the barge had buried the reef. “The reef creatures are now ten feet below a mound of sand that never used to be there. We were anchored in six feet of water where the charts show sixteen to eighteen. What little sticks out is covered in cyanobacteria—coral just can’t grow on shifting sand.”

For many, the most maddening part is that the barge’s cargo of sand and stones—intended for a major development—no longer matters. The damage has been done. Rope, metal sheets, and broken-up plastic continue to wash off the wreck, injuring corals that have anchored local fisheries and tourism for generations. Volunteers say the salvage is beyond their capabilities, but they refuse to sit idle while the reef deteriorates.

“These line nets are a real entanglement danger to whales and dolphins,” says Dr. Charlotte Dunn, President of the Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation. “So many ropes and materials were spilled on impact, and it’s still littered all around the site on the reef.”

For Mizell and her partners, lifting the barge itself is far beyond anything PIMS or volunteers could attempt. A full salvage would demand heavy‑lift cranes, specialized crews, and the owners’ insurance footing a substantial bill—none of which has materialized. Until that happens, the community is chipping away at the only part they can control: loose debris. Volunteers juggle ferry schedules to bring in scuba tanks, borrow boats to shuttle gear, and line up storage and disposal sites—then watch the forecast for a narrow window of calm seas.

Even after the wreck is gone, the reef will need years of hands‑on care—from replanting nursery‑raised elkhorn and staghorn corals to long‑term monitoring by PIMS’ Reef Rescue Network. As PIMS’ coral-restoration arm, the Reef Rescue Network unites dive shops, nonprofits, and marine scientists to cultivate endangered corals in underwater nurseries and “re-seed” them onto damaged reefs around the world.

“All of us—BNT, FRIENDS, BMMRO, local divers, homeowners, the cruising community—are pitching in,” says Mizell. “But we’re out here with mesh bags and volunteer boats. There needs to be a proper salvage operation.”

Despite daunting odds, the volunteers remain undeterred. Audrey Allgood and Garrett McQuiston, a young couple running charter trips in Abaco, volunteered to dive on the site. “It’s our backyard,” says Allgood, “and if we don’t act, who will?”

In a place where reefs protect coastlines, fuel the tourism economy, and support local fishermen, many wonder how a stranded tug and barge can remain lodged in a national park for over a year. Lawsuits may assign who pays the bill eventually, but in the meantime, volunteers say they will do everything possible to keep Fowl Cays National Park from suffering irreversible harm.